When trying to constantly 'feel good' backfires

Learn about how constantly chasing good feelings can backfire on you and make you feel even worse.

What’s the point of life?

There’s no correct answer to that question, but first, tell me if this sounds like you.

- You were a hyper-achiever in your 20s. You built a great career and earned a lot.

- You lived in a big city in which you could have a lot of wild experiences and built a robust social circle.

- As you’ve gotten older and your purchasing power has increased, you’ve been able to remove a lot of inconvenience from your life. Think: no more roommates, lots of Doordash, a really nice car, maybe even a big house.

- You’re well-traveled and have quite a few nice material possessions.

- You aren’t a caretaker for anybody. No kids, no elderly parents.

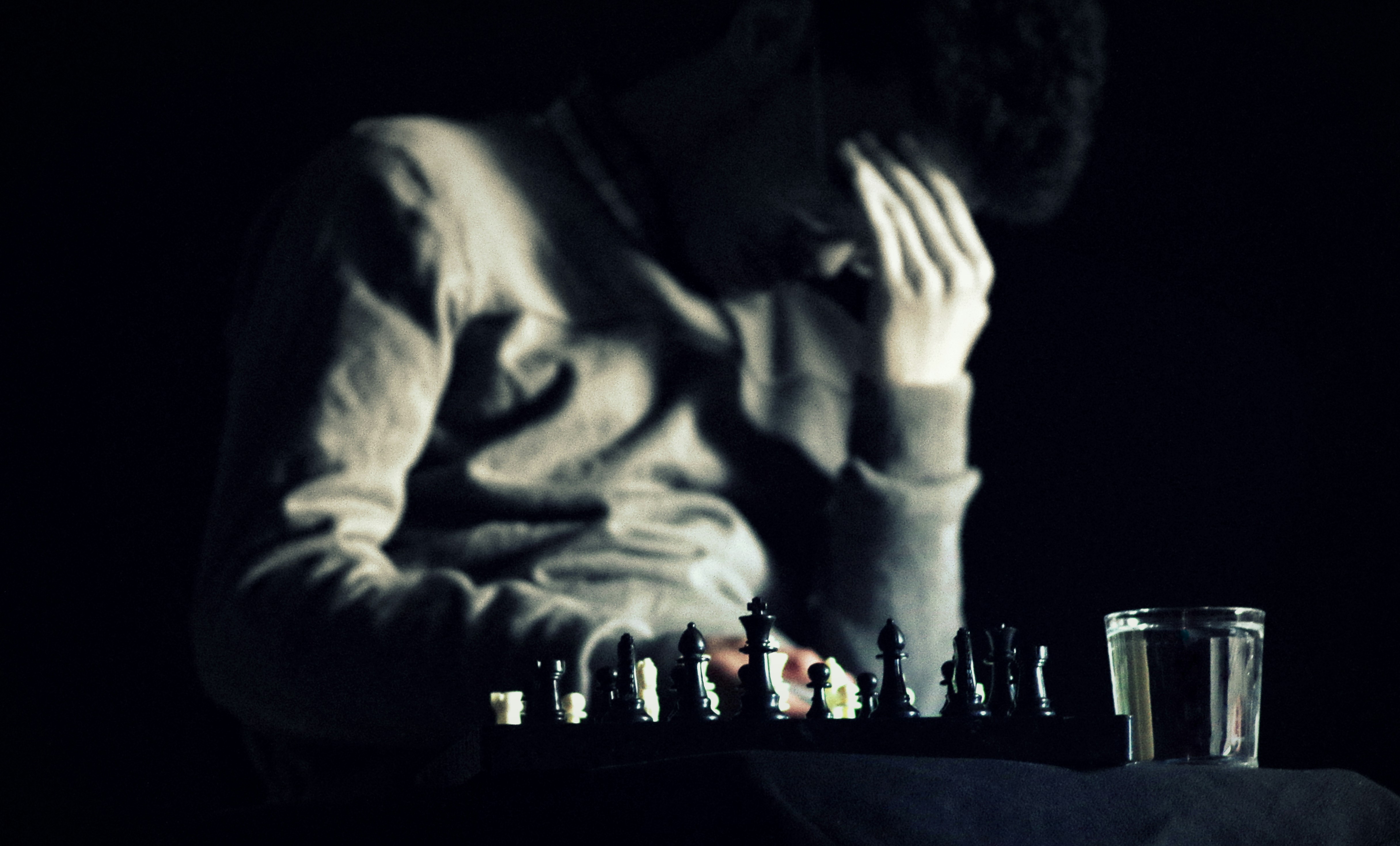

- Yet, despite having achieved all that, you encounter this low-grade, existential dread that seems to follow you like a shroud throughout the day.

If this is you, first—no shade. It was (and still is!) me to a degree, too. And it is the reality of most of my clients. Which is why I can pretty accurately predict that if you check most of these boxes, your answer to my question above is something like “the purpose of life is to enjoy it for the short period that we’re alive.”

I agree with you to a degree! But we have to talk about that last bullet—the sense of ennui that may or may not be following you throughout the day. Because it is in fact related to the above, and starts to appear when our life philosophy moves away from “generally trying to enjoy the ride” into something called hedonism.

Hedonism is a philosophy that essentially tries to maximize “feeling good” all the time. Typically it equates feeling good with pleasure, but you might also sub in comfort, joy, or happiness here too. Hedonism is a view that essentially says “I must feel good all the time!” and it is quite easy for a certain demographic (young to midlife overachievers with lots of purchasing power) to get sucked into it.

Hedonism makes us intolerant to pain and uncertainty

If you live from hedonism, you spend a lot of time micromanaging your day to make sure that you mostly feel good. We all have a natural, biological drive to run towards pleasure and run away from pain—that’s not quite what I’m talking about here. Somebody who is in hedonism needs to constantly feel good constantly, and if they don’t feel good, they spend a lot of time focused on why that might be and trying to “solve” for it.

Hedonists love to get high. Both in the literal, substance-abuse sense but also in the non-literal engagement of something called the hedonic treadmill. The hedonic treadmill is this pesky tendency we tend to have of returning to a baseline level of contentment after getting or achieving something we really want. Say you get promoted at work. That feels really good for about a month, but then the high wears off, you get bored, and you start gearing up for the next promotion. You can apply this same sense of constant striving to any material outcome—a house, a car, an achievement, etc.

Society dupes us into thinking that the next big piece of material achievement or wealth is the thing we really need to hold onto that good feeling forever. Which makes sense, because that’s a great way to build a capitalistic culture of hyper-consumerism.

But is it really true that if you felt good inside all the time that you’d live a full life? Let’s investigate.

A thought experiment—the pleasure machine

I’m stealing this from Philosophy 101, but the classic thought-experiment debunking hedonism tends to go like this. If you could hook yourself up to a machine that gave you constant pleasure and no pain for the rest of your life, would you do it?

Many of us have a visceral negative reaction to that idea. Hoarding only pleasure and avoiding pain feels like…not quite a life, right? It feels inherently wrong to insulate one’s self away from about 50% of the human experience.

Yet, we do this all the time in our daily lives. We frequently seek convenience, ease, comfort, and pleasure—whether in our daily choices or through substance use and abuse. And when we can’t get our fixes—i.e., we experience negative emotion or dissatisfaction—it’s not just a normal passing experience. It’s a capital P problem we must go investigate or fix.

In the abstract, we can grok that pain is a part of the equation of living, but when it comes down to actually experiencing said pain, we duck-and-hide. The real problem with hedonic living is that it makes us incredibly intolerant to pain, discomfort, and uncertainty, and those are all essential components of life. When we shy away from these feelings strictly because they don't feel good; our lives can become small, repetitive, and empty.

Think of the moments you’re most proud of in your own life. Could you have realistically achieved them if you weren’t able to experience discomfort, pain, and inconvenience? I’m assuming not. That’s because these feelings we want to run from are actually our greatest teachers. They catalyze our growth as humans and using our wealth or privilege to edit them out of our lives deprives us of the ability to grow, develop, and meaningfully change.

2 ways to step out of Hedonism

I’ll start with the advice you probably haven’t heard before. If you are fortunate enough to be able to live a hedonic lifestyle and you want out, then you need to create more productive, external suffering in your life.

Yes—your life coach is here telling you to go suffer. Because as you’ve discovered, hedonism doesn’t take suffering away, it simply moves it inside of you in the form of existential dread, worry, and angst. This is what I call ‘unproductive’ suffering. It does nothing to grow you, your community, or the world at large.

Productive suffering is you challenging yourself to do something hard strictly for the sake of doing it, or for the benefit of others. This is an important nuance that I really want to highlight. If you pursue a new challenge or goal, but it has a hard outcome attached to it that only benefits you, it’s not productive suffering—it’s just more striving.

Why? Because of our friend the hedonic treadmill. If challenging yourself looks like going to the gym to hit a physique goal, you will one day hit that goal and then your brain will quickly go “ok so what’s the next goal?” But if your goal is to just go to the gym because you value fitness and pushing yourself in a new way feels scary (and a bit exciting) then that is productive suffering! The hedonic treadmill thrives when you live for outcomes and achievements but cannot function at all when you do things you value simply for the sake of doing them.

More nuance—I’m not telling you to go do things you actively despise. The sweet spot here is something that you value but you’ve felt too scared, busy, or preoccupied to undertake as of late. Extra brownie points if this activity or commitment benefits people other than yourself. And If this activity is of sole benefit to you, it’s still fair game, but you need to be very careful to not let your brain attach to an outcome or an achievement associated with it.

The other way out of hedonism is the one you’ve heard already—gratitude. Being grateful for the many blessings we have already takes us off the hedonic treadmill because it breaks the illusion that having “more” of something will finally make us happy. But practicing gratitude can’t be a quick afterthought, it needs to be very intentional and very focused.

It’s not enough to just make a list of things you’re thankful for. I actually recommend my client pick 1 or 2 things, and then do a very detailed visualization about the person they were before that thing came into their life. Who were you before the 1-bedroom apartment, the promo, or the spouse, and what would that past version of you think about what you have now? Can you find the joy you had at the moment you got the thing you wanted and move closer to that feeling again?

Final words—contentment vs pleasure

I can’t prescribe a single life purpose to you, but I hope I’ve demonstrated that the goal of your life cannot be to “feel good all the time.” Many friends and clients have balked at that initially—am I saying that part of being human will always be misery and pain? Yes, and no.

Yes in the sense that there will never be a point in your life in which you never struggle or experience discomfort. Icky feelings are as much a part of life as all the good ones, too. And as demonstrated, there are consequences to trying to edit them out of life.

But still, there is nuance here, because what does it mean to “feel good?” I can reasonably tell you that pleasure, ecstasy, joy, and happiness—the more dramatic expressions of ‘good’—are never permanent. They are fleeting by design. The same is true for the dramatic expressions of ‘bad’—depression, panic, and misery, to name a few.

But what can stick around for a lot longer is what the Buddha called dukkha and its opposite, sukkha. It’s tough to translate these words outside of Pali, but you might think of dukkha as that ennui feeling we spoke about above—this general sense of soft dissatisfaction with life. We obviously don’t want that feeling, but it tends to show up when something is blocking us from living fully—including our own habits.

So, then, the goal is sukkha, which is something more like “ease” or “contentment.” You will not feel ecstatically blissful for most of your days, but you can certainly attain a level of quiet contentment that follows you in the background of your life even when things in external reality get hard or painful.

So, if you’re done with hedonism, don’t fret—I’m not saying you’ll never be able to hold onto good feelings again. I’m just saying the good that lasts is a lot softer than you may think.

.jpg)